Narratives are extremely powerful tools within a society. They help to define people’s perceptions of the world and establish national identities. Those who shape and control the flow of these narratives wield arguably the greatest form of political power. This is nothing new. Governments of virtually every country have to some degree used their national press to push desirable narratives. Policies are effectively sold to the public in this way.

The UK press undoubtedly wields considerable influence over public opinion. We repeatedly see voting outcomes being overwhelmingly influenced by certain publications in favour of political parties affiliated with those same publications. It could be argued that there is a case for legislation that would either curb the power of the press or prevent excessive political affiliation. The problem with this argument is that it is difficult to define the limits of the press’ political influence in such a way as to preserve journalistic freedom. This debate has been raging since the dawn of the printed word yet in recent history some progress had been made.

In 1966 the UN drafted the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in order to establish universal guidelines of conduct for member states. Most pertinent to the press are Articles 19 and 20.

Article 19

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

- The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

- For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

- For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Article 20

- Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.

- Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.

The UK openly prides itself on maintaining freedom of the press by opting for self regulation. Some national publications such as the Guardian, Financial Times and Standard have their own in-house editorial codes and complaints handling. Others have signed up to one of two regulatory bodies: 1) the most prevalent, industry backed Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) and 2) IMPRESS which recently became the UK’s first approved press regulator. A crucial difference between them is that the IPSO is funded by the papers it is meant to be regulating while IMPRESS is under no industrial obligation and can make its own rules. No national newspaper has yet signed up to IMPRESS, most are signed up to IPSO.

Articles 19 and 20 of the ICCPR are intended to be at the heart of each member state’s press regulatory bodies. As a permanent UN member state, the UK is theoretically obliged to uphold them. In practice, it has been openly defying them for decades. Although the IPSO has proven reasonably effective on regional matters it has utterly failed to hold national papers accountable for their ever increasing abuses of journalistic freedom.

To examine each of the major narratives of today would be too exhaustive so here the focus is on the incitement of hatred and discrimination; a common tactic used in the ancient ‘divide and conquer’ narrative.

The UK press deliberately incites hatred and discrimination

Numerous articles published by The Sun and The Daily Mail in particular cannot be reconciled with the provisions of Article 20. A 2016 report from the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) concluded among other things that ‘some reporting on immigration, terrorism and the refugee crisis was “contributing to creating an atmosphere of hostility and rejection”.’ The report cited the infamous Katie Hopkins Sun column in which she referred to refugees as “cockroaches” along with ‘the same newspaper’s debunked claim over “1 in 5 Brit Muslims’ sympathy for jihadis”.’

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights denounced The Sun over the Katie Hopkins column:

“this vicious verbal assault on migrants and asylum seekers in the UK tabloid press has continued unchallenged under the law for far too long. I am an unswerving advocate of freedom of expression, which is guaranteed under Article 19 of the ICCPR, but it is not absolute. Article 20 of the same covenant says: ‘Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.’”

The matter was put before the IPSO who dismissed it on the grounds that “migrants as such are not a group that can be discriminated against”, as chief executive Matt Tee put it, “and actually in our terms for it to be discrimination, the complainant would have had to show that an individual or a group of individuals were discriminated against by that phrase.” Tee added that the Hopkins article was an opinion piece not a statement of fact. He claimed that suggestions of inciting racial hatred were a legal matter to be handled by the police.

The fact that human beings escaping wars in Syria and elsewhere were compared to cockroaches in a national publication was deemed to be ‘in poor taste’ but apparently acceptable. Whether or not The Sun was in breach of ICCPR’s Article 20 was irrelevant. Although there was a significant public backlash against Hopkins and her article, this incident set a crucial precedent as to what those pushing hatred could get away with in the national press.

The refusal of the IPSO to denounce any of the blatant and relentless advocacy of hatred in papers like The Sun and Daily Mail, even in such a clear case as the Katie Hopkins column, was a worrying sign of escalation. The IPSO casually dismissed the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights thereby shirking the UK’s commitments to the global community.

The Hopkins case occurred alongside the approval of UK air strikes in Syria, the political murder of British MP Jo Cox, and the EU referendum. Following the latter was a 41% increase in hate crimes. Over the same period, there was a steep increase in government actions making it more difficult for refugees, migrants and asylum seekers to live in the UK despite the desperate needs of so many people fleeing war in Syria. Stoking the fires of hatred in such a climate is both extremely dangerous and terribly irresponsible; intentionally or otherwise.

Change the language

We have seen attempts to cast others as sub-human many times before in language used by the Nazis in Germany, the Hutus in Rwanda and the many colonial proponents of slavery. Each employed this language to ‘open the door for cruelty and genocide.’

If history has taught us anything we must find ways to curb the language of hatred used by the press. Allowing it to continue enables the normalisation of dehumanisation. It also helps to sell policies of division that are exploited for wealth by the few at the expense of the many. Since we clearly cannot rely on self regulation to hold the press accountable we are forced to explore alternatives. Unfortunately the current government is actively preventing this from taking place having for instance abandoned the second phase of the Leveson enquiry.

At the moment our world is gripped by the COVID-19 crisis. The role of the UK press has been critical here too and many questions have already been raised as to whether certain publications have acted irresponsibly or even against public interest. Comparing the output of publications that are considered left-leaning with those that are right-leaning reveals narratives that are frequently in total opposition on the same issues. People often don’t know who or what to believe. Trust between the public and its institutions has broken down badly. The press plays a substantial role in all of this.

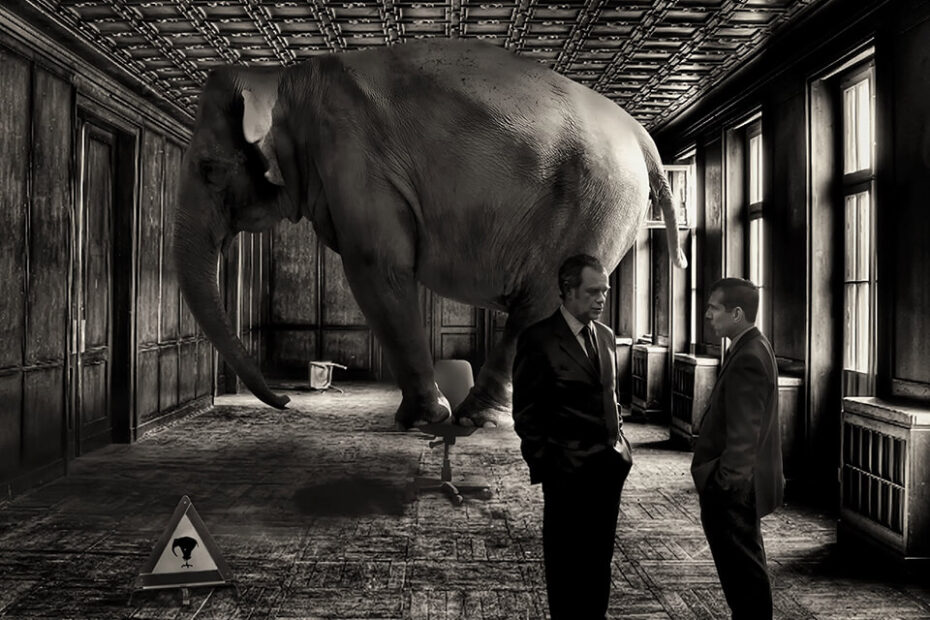

Until we have a system of regulation that truly respects the ICCPR with appropriate checks and balances the UK press will continue to be the elephant in the political theatre. Without immense public pressure it is unlikely that anything will change. Public awareness therefore needs to be raised somehow outside of mainstream media. People need to become more aware of what these narrative are, what they mean and how they are being used as tools of manipulation. With enough public pressure it might be possible to force at least some publications to shift away from the IPSO towards IMPRESS.